Blog

Finding Purpose for a Good Life. But Also a Healthy One.

My favorite medical diagnosis is “failure to thrive.”

Not because patients are failing to thrive — that part makes me sad. But because of the diagnosis’s bold proposition: Humans, in their natural state, are meant to thrive.

My patient, however, was not in his natural state. Cancer had claimed nearly every organ in his body. He’d lost a quarter of his body mass. I worried his ribs would crack under the weight of my stethoscope.

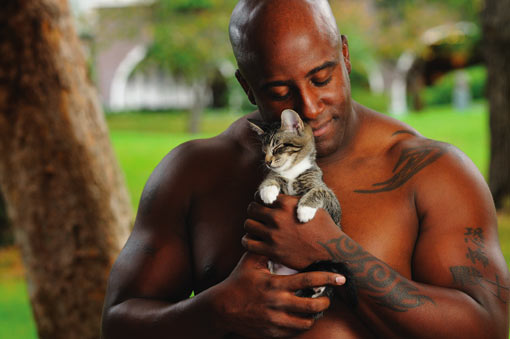

“You know,” he told me the evening I admitted him. “A few years ago, I wouldn’t have cared if I made it. ‘Take me God,’ I would’ve said. ‘What good am I doing here anyway?’ But now you have to save me. Sadie needs me.”

He’d struggled with depression most of his life, he said. Strangely enough, it seemed to him, he was most at peace while caring for his mother when she had Parkinson’s, but she died years ago. Since then, he had felt aimless, without a sense of purpose, until Sadie wandered into his life.

By

Sadie was his cat.

Only about a quarter of Americans strongly endorse having a clear sense of purpose and of what makes their lives meaningful, while nearly 40 percent either feel neutral or say they don’t. This is both a social and a public health problem: Research increasingly suggests that purpose is important for a meaningful life — but also for a healthy life.

Purpose and meaning are connected to what researchers call eudaimonic well-being. This is distinct from, and sometimes inversely related to, happiness (hedonic well-being). One constitutes a deeper, more durable state, while the other is superficial and transient.

Being a pediatric oncologist, for example, is not a “happy” job, but it may be a very rewarding one. Raising a family can be profoundly meaningful, but parents are often less happy while interacting with their children than exercising or watching television.

Having purpose is linked to a number of positive health outcomes, including better sleep, fewer strokes and heart attacks, and a lower risk of dementia, disability and premature death. Those with a strong sense of purpose are more likely to embrace preventive health services, like mammograms, colonoscopies and flu shots.

And people with high scores on measures of eudaimonic well-being have low levels of pro-inflammatory gene expression; those with high scores on hedonic pleasure have just the opposite.

Doing good, it seems, is better than feeling good.

One study analyzed how having purpose influences one’s risk of dementia. Researchers assessed baseline levels of purpose for 951 individuals without dementia, then followed them for seven years, controlling for things like depression, neuroticism, socioeconomic status and chronic disease. Those who had expressed a greater sense of purpose were 2.4 times less likely to develop Alzheimer’s, and were far less likely to develop even minor cognitive problems.

Another study followed more than 6,000 individuals over 14 years and found that those with greater purpose were 15 percent less likely to die than those who were aimless, and that having purpose was protective across the life span — for people in their 20s as well as those in their 70s.

Having purpose is not a fixed trait, but rather a modifiable state: Purpose can be honed through strategies that help us engage in meaningful activities and behaviors. This has implications at both the dinner table and the hospital bed.

A recent randomized control trial compared the effect of “meaning-centered” versus “support-focused” group therapy for patients with metastatic cancer. Patients in the support groups met weekly and discussed things like “the need for support,” “coping with medical tests” and “communicating with providers.”

Patients in the meaning-centered groups focused instead on spiritual and existential questions. They explored topics like “meaning before and after cancer,” “what made us who we are today,” and “things we have done and want to do in the future.” Meaning-centered patients experienced fewer physical symptoms, had a higher quality of life, felt less hopeless — and were more likely to want to keep living.

Other research suggests that school programs that allow students to discuss positive emotions and meaningful experiences may enhance psychological well-being, and protect against future behavioral challenges. But this isn’t how we usually operate. We instead assume that anxiety and depression are problems to be treated — not that emotional resilience and human flourishing are states to be celebrated.

What’s powerful about these conversations is not just that they can help cancer patients through treatment or help teenagers build resiliency — they can also help the rest of us. We should all consider asking ourselves and our loved ones these questions more often.

During my most trying months of medical school, I met every Sunday evening with three friends. Phones off, lights dim, wine glasses full. We shared the most challenging and most rewarding moments of our weeks. These conversations helped each of us glean — or perhaps create — meaning in challenging, sometimes traumatic, experiences: the death of a child we’d cared for; abusive language from a superior; the guilt of committing a medical error.

It was in these sessions that I chose my specialty, decided to apply to policy school, and vowed to reconnect with a lost friend.

Meaning grows not just from conversation, of course, but also from action. One recent study randomly assigned 10th graders to volunteer weekly with elementary students — to help with homework, cooking, sports, or arts and crafts — or put them on a wait list.

Teenagers who volunteered had lower levels of inflammation, better cholesterol profiles and lower body mass index. Those who had the biggest jumps in empathy and altruism scores had the largest reductions in cardiovascular risk.

Engaging in these kinds of activities may be most important for individuals whose identity is in flux, like parents with children leaving for college or workers preparing for retirement. A program run by Experience Corps, an organization that trains older adults to tutor children in urban public schools, has shown marked improvements in mental and physical health among tutors. The improvements included higher self-esteem, more social connectedness, and better mobility and stamina. (The children do better, too.)

This work hints at an underlying truth: Finding purpose is rarely an epiphany, nor is it something you pick up at the mall or download from the app store. It can be a long, arduous process that requires introspection and conversation, then a commitment to act.

The key to a deeper, healthier life, it seems, isn’t knowing the meaning of life — it’s building meaning into your life. Even if meaning is a four-legged friend named Sadie.